Why do even some of the highest of high-skilled foreign nationals put off starting their EB-2 National Interest Waiver case? Could it be because they think delaying the case won’t hurt its strength? They might think this, because they lack of immigration expertise and experience. Look, they’re experts in some field, whether it be science, engineering, business, or something else. And they (often) erroneously think they have the mental bandwidth to develop the expertise necessary to wisely make many important immigration judgments, including whether they will harm their chances of getting an EB-2 NIW waiver if they delay applying for one.

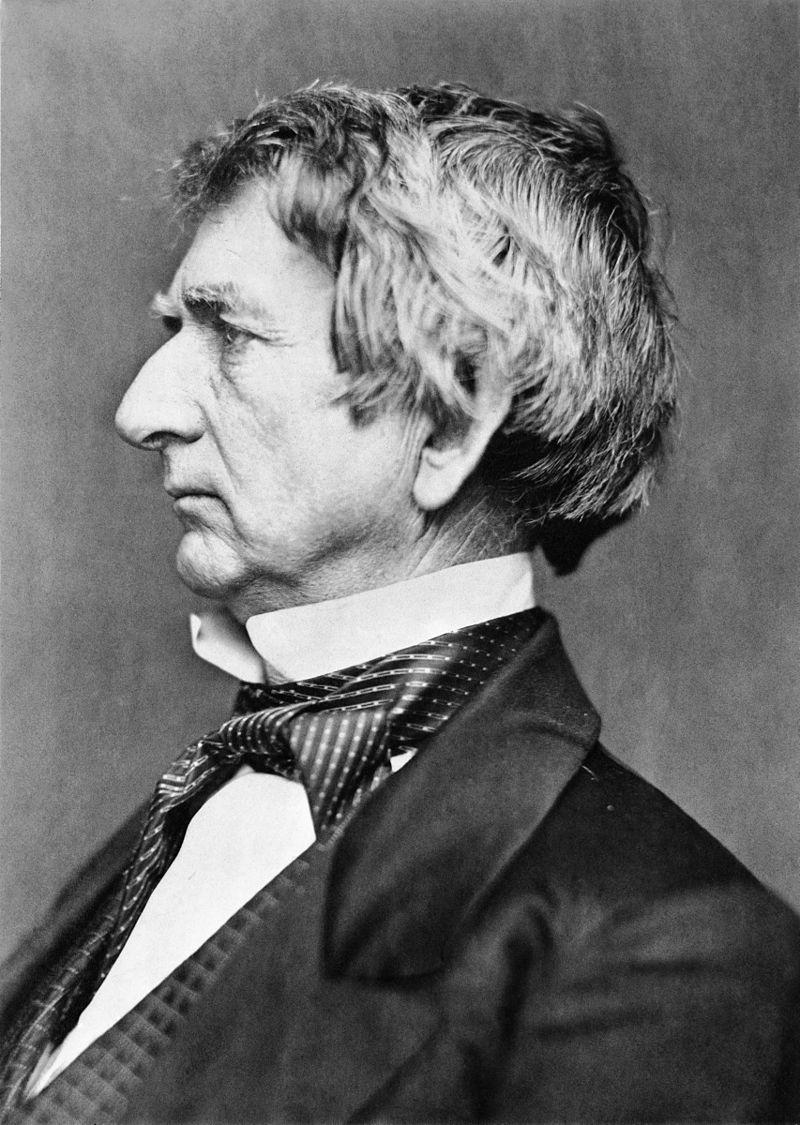

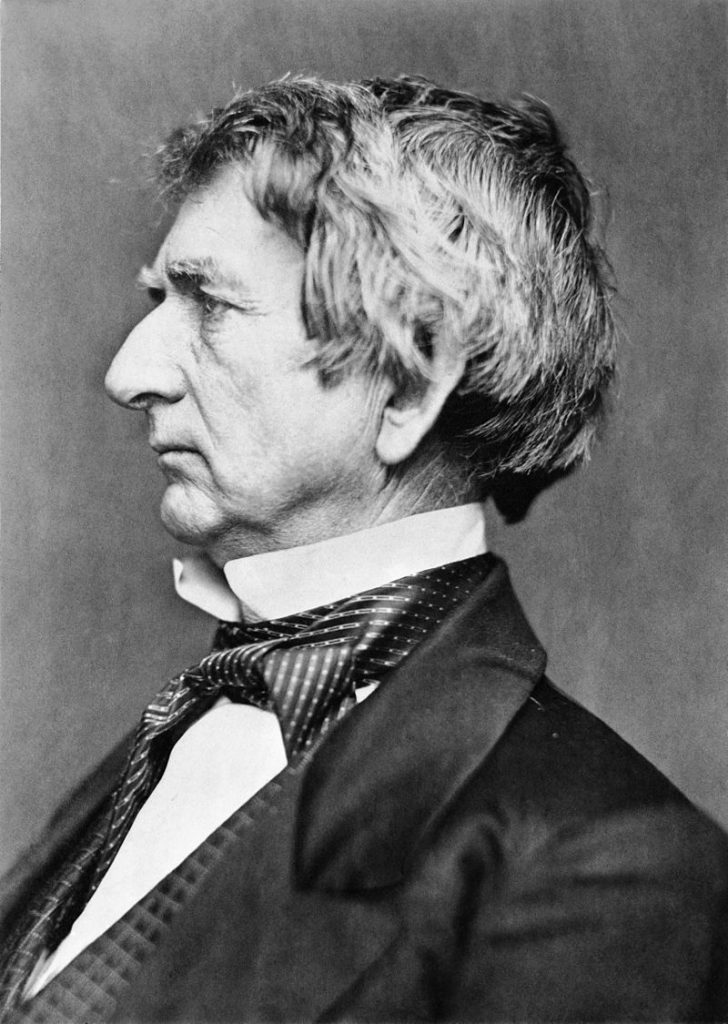

They should take a page out of US President Abraham Lincoln’s playbook.

There is an fitting story told by historian Doris Kearnes Goodwin, in her book Team of Rivals, about Lincoln and his Cabinet.

Some context may be useful to understand the story. The story takes place just after the start the US Civil War, a war sparked by differences between the North (the Union) and South (the Confederacy) over slavery.

Goodwin writes:

With more than enough troubles to occupy him at home, Lincoln faced a tangled situation abroad. A member of the British Parliament had introduced a resolution urging England to accord the Southern Confederacy belligerent status. If passed, the resolution would give Confederate ships the same rights in neutral ports enjoyed by Federal ships. Britain’s textile economy depended on cotton furnished by Southern plantations. Unless the British broke the Union blockade to ensure a continuing supply of cotton, the great textile mills in Manchester and Leeds would be forced to cut back or come to a halt. Merchants would lose money, and thousands of workers would lose their jobs.

[Secretary of State] Seward feared that England would back the South simply to feed its own factories. While the “younger branch of the British stock” might support freedom [of slaves], he told his wife, the aristocrats, concerned more with economics than morality, would become “the ally of the traitors.” To prevent this from happening, he was “trying to get a bold remonstrance through the Cabinet, before it is too late.” He hoped not only to halt further thoughts of recognition of the Confederacy but to ensure that the British would respect the Union blockade and refuse, even informally, to meet with the three Southern commissioners who had been sent to London to negotiate for the Confederacy. To achieve these goals, Seward was willing to wage war. “God damn ’em, I’ll give ’em hell,” he told [a prominent US senator], thrusting his foot in the air as he spoke.

On May 21, Seward brought Lincoln a surly letter drafted for [the US envoy to the United Kingdom] Charles Francis Adams to read verbatim to Lord John Russell, Britain’s foreign secretary. Lincoln recognized immediately that the tone was too abrasive for a diplomatic communication. While decisive action might be necessary to prevent Britain from any form of overt sympathy with the South, Lincoln had no intention of fighting two wars at once.

Lincoln recognized the limits of his and the country’s bandwidth; he realistically appraised what he and his nation had the resources to do. And then he acted accordingly.

Goodwin continues the story:

[T]o mitigate the harshness of the draft, [Lincoln] altered the tone of the letter at numerous points. Where Seward had claimed that the president was “surprised and grieved” that no protest had been made against unofficial meetings with the Southern commissioners, Lincoln wrote simply that the “President regrets.” Where Seward threatened that “no one of these proceedings [informal or formal recognition, or breaking the blockade] will be borne,” Lincoln shifted the phrase to “will pass unnoticed.”

Most important, where Seward had indicated that the letter be read directly to the British foreign secretary, Lincoln insisted that it serve merely for Adams’s guidance and should not “be read, or shown to anyone.” Still, the central message remained clear: a warning to Britain that if the vexing issues were not resolved, and Britain decided “to fraternize with our domestic enemy,” then a war between the United States and Britain “may ensue,” caused by “the action of Great Britain, not our own.” …

Thus, a threatening message that might have embroiled the Union in two wars at the same time became instead the basis for a hard-line policy that effectively interrupted British momentum toward recognizing the Confederacy. Furthermore, France, whose ministers had promised to act in concert with Britain, followed suit. This was a critical victory for the Union.

Many high-skilled foreign nationals fight two or more wars at the same time. They spend time working in the profession in which they have achieved so much (war #1)–and they also make hugely important immigration decisions that require analysis (war #2), such as whether they should start their high-skilled immigration case immediately or delay.

The problem is that many high-skilled immigrants lose the second war: they make choices that paralyze their immigration case. They should instead take the page from Lincoln’s playbook.